I have a talk I give on writing called The Storyteller’s Toolbox. I’ve given versions of it at Georgia Tech, Georgia State University, the CONjuration fantasy fan convention, the Broadleaf Writers Conference, and a few other places like that. There’s a video version online. One of the questions that just about always comes up is this: where do you start?

Novels begin with an idea, obviously. Ideas are easier than you think. I personally have more story ideas than I have years to live. If you’re stuck, one secret is just to think of a character (or characters, just it’s best to start with one or two) that you care about. Next, think of where they live, How does the world of the story shape them? Then, think of something they want. Finally, who or what doesn’t want them to have it? Now you have a character, setting, adversity, and conflict. Boom! That’s an idea.

Ideas are easy. Execution is hard. Even when you know your story backward and forward, and you know your characters better than you know your best friends, getting started is still the hardest part.

A while back, I wrote a blog on some of my very favorite first sentences in literature. I was thinking to write an updated version of that post, but to be honest, I think the first list still holds up. That’s the thing about favorites; they stick around. A favorite isn’t transient; it’s not a fad. Things that touch the heart linger there.

It has, nonetheless, got me thinking. First sentences are, of course, critical. It’s your chance to hook a casual browser in a bookshop, of course. It might just be the hook that makes your book somebody’s favorite. The nightmare scenario is just the opposite. A dull first sentence might make someone put the book down and never pick it up again. So no pressure.

In talking with my own editor and publisher, Lou Aronica of The Story Plant, I’ve noticed a trend. Lou always begins his novels with a character—either the main character or one of the main characters. I, on the other hand, always start with place. That’s not something that, I think, either of us decided to do consciously. Nonetheless, it’s how it worked out.

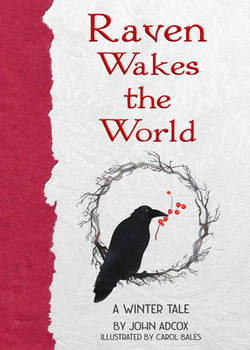

Raven Wakes the World, the first of my Winter Tale novels, opens thusly:

It was cold, and all the world was white.

Snow covered the stony island, and from where Katie Mason stood, the icy landscape blended into the overcast winter sky, white melding into frigid white, without shape, distance, or horizon. It was the white of a barren canvas, or fallow stone, art stillborn. The only change from the stunning, melancholy monotony of white was a single black bird, a large crow, or raven, maybe, that circled overhead once, twice, and three times before winging away over the still sea toward the frozen rocks of the mainland.

In this case, the place is a mirror for the main character’s inner state, as well as the place where the story takes place. It also starts to subtly suggest the idea that Katie is an artist. To me, though, the reader is oriented immediately.

My second Winter Tale, Christmas Past, opens with this first sentence:

I was in London when I first heard about Sam’s ghost.

We don’t yet know who the “I” is, but we know where she is, and at least a little about what kind of story we’re in for. London, I think, also suggests a certain mood.

My novel Blackthorne Faire begins with a scene that takes place a few decades before the main story:

In later years, the vast suburban sprawl of Atlanta will bleed outward like kudzu to cover the hills and hollows that surround the O’Brien farm with subdivisions and mini-malls. But not yet. Now the city is too much in the future to be a part of life here. It is distant, a dream, like New York or Paris, or the Pyramids in Egypt. Now the southern hills burn with rich color, fire and rust—a thousand million shades of orange, yellow, and apple red set against a deep and enduring background of evergreen beneath the brilliant, sapphire blue sky of an autumn long past. The old year has dressed in its finery for one last hurrah before the winter frosts come to soothe it away to memory. Breathe! Taste air crisp and heavy with the scents of pumpkin, sweet applewood smoke, dying leaves, and the last wild Georgia blackberries. Breathe, breathe, child, and autumn fills you like spiced wine.

Here, my goal, conscious or otherwise, was to immerse the reader in the world of the story. It’s something I learned from at least two of my book grandparents, J.R.R. Tolkien and Ray Bradbury. The Hobbit begins with this:

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hold, and that means comfort.

The place (a hole) is introduced first, and then the character (a hobbit). But professor Tolkien then goes on the describe the hole before the hobbit. The key, though, is that the place isn’t just orienting the reader, although it certainly does that. It’s using place to define the character, a trick made famous in Wuthering Heights.

It’s also Shakespeare’s approach in Romeo and Juliet:

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene….

Shakespeare is orienting his audience. Where are we? That happens before the leads are introduced. In fact, even the mention of the feuding families, “the two households both alike in dignity,” sets up the milieu of the story. The feud is a part of the world where that story takes place.

Looking back, I think my opening of Blackthorne Faire was probably influenced most by the great Ray Bradbury. This, for example, is how he opens his wonderful novel Something Wicked This Way Comes:

First of all, it was October, a rare month for boys. Not that all months aren’t rare. But there be bad and good, as the pirates say. Take September, a bad month: school begins. Consider August, a good month: school hasn’t begun yet. July, well, July’s really fine: there’s no chance in the world for school. June, no doubting it, June’s best of all, for the school doors spring wide and September’s a billion years away.

But you take October, now. School’s been on a month and you’re riding easier in the reins, jogging along. You got time to think of the garbage you’ll dump on old man Prickett’s porch, or the hairy-ape costume you’ll wear to the YMCA the last night of the month. And if it’s around October twentieth and everything smoky-smelling and the sky orange and ash gray at twilight, it seems Halloween will never come in a fall of broomsticks and a soft flap of bedsheets around corners.

That’s all about setting. Sure, there’s no mention of Green Town, the city where the story actually takes place. But the story is awash in autumn. I’d argue that autumn is the setting even more than the town. Every page is drenched with falling leaves and the coming chill of Halloween. Ray has immersed us in the world and feeling of the story long before any hints of plot or character are introduced. We know right where we are when the story starts. It’s a terrific way to open the door to a story.

In Something Wicked This Way Comes, autumn is almost a character in the story, like the moors in Wuthering Heights. It’s omnipresent. I like to hope that the renaissance festival in Blackthorne Faire is likewise itself a character of sorts. If I’ve done my work well, it’s a place readers will fall in love with as much as the actual characters do. The festival itself doesn’t appear in those opening lines, but the grounds were it will exist someday do. Even Renaissance fairs can have a backstory.

Now then. Here’s the first sentence from Blue, my favorite of Lou’s novels:

Images whirred by. Chris sat on the sofa opposite the television, the remote in his hand. He didn’t intend to use it; he just let the machine continue fast-forwarding.

Here, Lou is starting with a lead character. There’s no need to give us that sense of place; just from that one line, we’re picturing any (or every) middle-class living room anywhere in America. We have a shelf of clichés in our brain, and we’re already conjuring up TV sets, old sofas, and wood paneling. We’re oriented. There’s also action. Note that Lou doesn’t say that Chris let the machine fast-forward. It continues fast-forwarding. So Chris has been in that spot for a while. The question now is why is this guy stuck? Why is he simply sitting and letting images play?

So Lou as given us a door into the story through a character. And he’s done it deftly, with just a few sketched lines. We already know where we are, who at least one character is, and what sort of problem he might be facing. All that deepens as the story builds. As I mentioned, Lou always opens his stories with a character.

Now, Lou and I both believe that character is the single most important part of a story, at least in our own work. There are exceptions, of course—some novels are more plot-driven than character-driven. I don’t think anyone reads The Da Vinci Code to get a deeper look into Robert Langdon’s soul. That said, I can’t think of a single book that I’d call a life-long favorite that is story-driven without at least also being character-driven. Characters make us care. Sometimes, they can show us ourselves more truly than any mirror can.

Nonetheless, I have always begun with place—but certainly not because I think it’s more important. This wasn’t a conscious decision, mind. It’s just how it’s turned out. Even my newest, Makeup Test, (coming in November) begins by putting the reader in the setting of the story:

In Atlanta, the best winter days were bright and sunny, and occasionally, very occasionally, snowy. The worst were gray, wet, cold, and miserable. The morning when Janie Mason’s wish came true was one of the worst of all—especially gray, decidedly wet, numbingly cold but just above freezing, and utterly miserable. Also, it was Monday.

The viewpoint character for this scene isn’t even introduced until the second paragraph.

I have no real idea why I do that—why I start with place. Until very recently, I wasn’t even aware that it’s something I do. As I mentioned, I like to orient the reader. They’ve just been plopped down into a new world—a world of story. It’s fair for them to ask: where the heck am I?

Another, and perhaps truer, reason is that place, not character, was what drew me, the child I was and remain, to the first books I fell deeply in love with—the books that (again, consciously or otherwise) shaped me as a reader and a writer. The are the books that taught me what it means to be utterly lost in a story. I’m thinking of the chocolate factory in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the secret headquarters in the Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators books, and, of course, most intensely of all, the marvelous land beyond the wardrobe in The Chronicles of Narnia and the wonderful hole in the ground in which lived The Hobbit. Our first loves define us as much as the spiraling chains of knowledge that make up all the cells in our bodies.

So, how about you, o readers and writers? Where do your favorites begin?

More of a case of making a noise to draw the attention and piqué curiosity than a setting or significant character. I’ve done it several times over the years, including in one of the novels I’m working on currently, SPORES.

James A. Moore

For reasons unknown, this post cut itself down from a longer post, so let’s try this again:

What I was trying to say is that on several occasions I have started novels off not with a significant character or setting, but with the proverbial BANG! In the case of my novel FIREWORKS, I literally started off with a character who is never seen again watching as a UFO scrambles across a government satellite display and immediately follow through with a man fishing on a lake, who has the unfortunate fate of watching the UFO crash into that lake. It is the last thing he ever sees.

I am not alone in this. I have seen other writers do the same thing. It’s not the place, it’s not the person, it’s the event that opens the story. Witnessed or merely described.

More of a case of making a noise to draw the attention and piqué curiosity than a setting or significant character. I’ve done it several times over the years, including in one of the novels I’m working on currently, SPORES.

James A. Moore

More of a case of making a noise to draw the attention and piqué curiosity than a setting or significant character. I’ve done it several times over the years, including in one of the novels I’m working on currently, SPORES.

“The isle of Gont, a single mountain that lifts its peak a mile above the storm-wracked Northeast Sea, is a land famous for wizards.” — A Wizard of Earthsea, Ursula K. Le Guin.

She does mention her character, Sparrowhawk, in the first paragraph, but she begins with place.

Another favorite of mine: “At dawn one still October day in the long ago of the world, across the hill of Alderley, a farmer from Mobberley was riding to Macclesfield fair.” — The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, Alan Garner

Thanks, gents! Bill, great examples. Those are gateways to get the reader lost in the story.

Jim, would you say those are more plot-driven stories?

Not at all, I would actually ay I’m more about characters than plot, though both are very important to any story.

“First of all, it was October, a rare month for boys.”

Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury.

So good.

Such an inspiration!