When I was in the third or fourth grade, I met a professional author for the first time. It happened to be one of my very favorites, Wylly Folk St. John, who was signing books at the Rich’s Department Store at North Dekalb Mall. This was back when Rich’s, North Dekalb Mall, and book sections in big department stores were all still things. By the way, I mentioned the great Wylly Folk St. John in my last blog post, and I was delighted to hear that so many of you also remember her books fondly.

That was right about the time when the notion of writing my own books had first started to occur to me. The problem was, I had no idea how to start. So when I got through the line and had my chance to speak to one of my first literary heroes, I had to ask: “Where do you get your ideas?” She smiled and told me, “from my grandchildren, mostly.” Then she signed my books. I still have them.

To be frank, that answer wasn’t a lot of help. First, I didn’t really believe, even then, that her grandchildren were out solving mysteries or finding lost treasures. Second, it didn’t tell me a darn thing about how to find ideas of my own, especially since I didn’t have grandchildren.

The biggest issue, I think now, was that I wasn’t asking the right question. What I should have asked Wylly Folk St. John was this: how do you shape a spark of an idea into a story? Not that I really think she’d have had time to answer at a book signing at Rich’s, not when there was still a line. Because the truth is, ideas are easy. They’re a dime a dozen and any other cliché you can think of (it’s okay to use a cliché when you’re all self-aware about it). Turning an idea into a story, yeah, that’s the hard part.

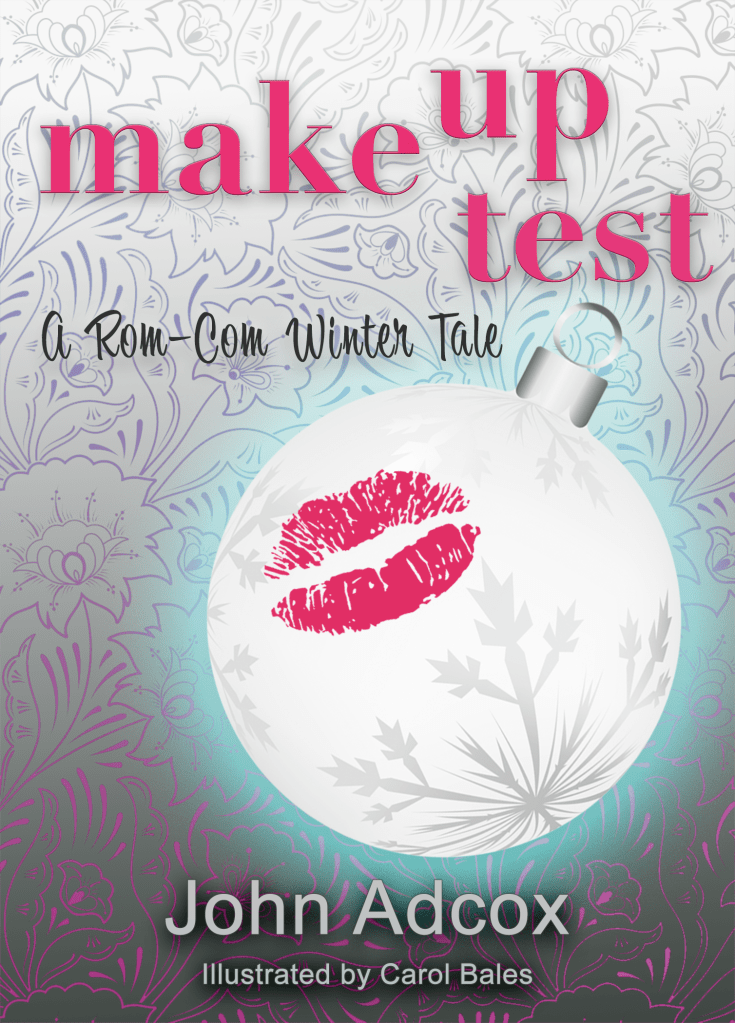

You can find ideas anywhere. I got the idea for my next novel Makeup Test: A Rom-Com Winter Tale, the first time I visited my girlfriend’s (later my wife’s) bathroom and saw all the makeup, with names like Vanishing Creme, Concealer, and (I swear this is real) Antigravity Lift Cream. To a guy like me, it was alien territory. I got the idea for the next Winter Tale, Incandescent (the one I’m writing now), from a thread on Facebook in which women were asking each other, “Who’s your book boyfriend?” They were talking about the characters they wished they could have a crush on. (#MrDarcy) It made me wonder . . . what if it was the other way around? What if a character was slowly falling in love . . . with the reader? Huh.

Singer/Songwriter Mike Cross once saw an old man get on a bus with a bouquet of flowers, and wondered who he was and what his story might be. Mike Cross turned that musing into one of the loveliest songs I’ve ever heard. Mike Cross didn’t know anything about the actual man. But from that one encounter, he wove a character and a story. Anything, and I mean pretty close to everything, can spark an idea for a story. With all sincerity, I have more book ideas than I have years to live.

So how do you structure and build a whole story? That’s a question I’ve been thinking about for a very long time. For me, I think, once the hint of an idea has jumped into my brain, the next step is to think of a character. Is the story about makeup with weird sounding names that sound almost magical? Well, who would wear that makeup? Why? What do they want? A character who wants something is a good place to start crafting a story.

Now, flesh that character out. Where do they live? Where do they work? Who are their friends? All of these details shape the character. I don’t know for certain, but I imagine this is where Wylly Folk St. John’s grandchildren helped her. Without a character, there’s no story. This doesn’t happen instantly. But the more you think about those characters as you go about your day, the more they come alive for you.

In fact, even if you don’t have that initial spark of an idea, you can usually find one by starting with a character and imagining their world, just like Mike Cross did. Start with a friend you knew in school, maybe, or someone you spotted in a coffee shop. Or, I don’t know, think of a Native American medicine woman or an astronaut.

Then, make them yours. What makes them unique? What are their strengths? What are their flaws? How are they broken?

After that, the most important question is this: what does that character want? Love? Adventure? A lost treasure? Not to die? Good start. The next question is, who (or what) doesn’t want the character to have what they want? Now you have an adversary, and from there, conflict. Remember, the adversary doesn’t have to be a villain, a Darth Vader (although that’s certainly an option). If your character wants to scale a mountain, the mountain itself, and all the natural dangers it represents, is the adversary. In fact, the adversary doesn’t have to be an external force at all. In Good Will Hunting, for example, Will Hunting is his own adversary. All (or most) of the primary conflict in the story is with himself.

When you have an idea, a main character (or an ensemble—hey, it’s your story, go nuts), an adversary, and conflict, you’re well on your way to a story. That’s not to say the idea will always work. Sometimes, you’ll roll the idea around and realize there isn’t a story there after all, or at least not one that you care about enough to tell. Maybe the characters that came to mind don’t excite you, or maybe there’s just not enough conflict and tension to weave a story around. Maybe the idea is just not about something that means enough to you. That’s okay. Just go back to the drawing board. Or put in on the shelf until it does excite you.

When you find the idea that does excite you, well, after that, it’s all about structure. Ideas are easy; stories are hard. That’s where the real work begins. But also, I think, the fun.

When I was in third or fourth grade, I met the Banana Splits at Toys R Us. I did not ask them where they got their ideas. Too bad; they might have had some crazy answers.